on November 28, 2012 by James T. Kirk Bio

(This chapter excerpt takes place following Jim Kirk’s second tour of duty aboard the U.S.S. Enterprise, 2271-2276).

EXCERPT OF CHAPTER 10: PROMISES AND HOPES

PART ONE

After another five-year tour in space, Jim Kirk found that his return home to the Admiralty was not what he expected or wanted. Rather than an opportunity to relax, set policy and steer the course of interstellar exploration, he instead found a massive skein of red tape, useless bureaucracy and petty, internecine clique’s bent on salvaging power and influence for themselves. Few of them appreciated the suggestions and direction of the “immortal” James T. Kirk. His own myth now constituted a river running against him.

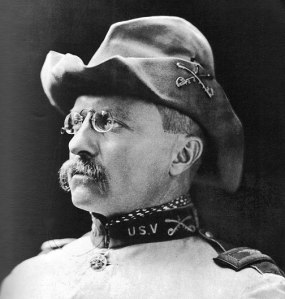

Star Fleet Headquarters, circa 2276, just as Jim Kirk was returning from his second tour as captain of the Enterprise.

Kirk should have been well aware of the structure of Star Fleet and Federation bureaucracy; he had now spent ten years dealing with it as a commander in the field, and a further two years as chief of Star Fleet operations. However, he never considered himself part of the old-guard hierarchy, no matter how deeply ingrained he was in the power structure. (“Sometimes I think that Star Fleet Command is the greatest conglomeration of dunsels ever assembled anywhere in the universe,” he once wrote to a friend after a particularly contentious policy meeting.)(1) More than once Kirk himself was nearly a casualty of the gridlock between the leadership of the Federation Council and Star Fleet Command. During a diplomatic mission to the planet Gideon in 2268, he was secretly kidnapped and used in a biological experiment that was designed to kill millions of the indigenous population. When the Enterprise requested latitude to search for their captain on Gideon, Federation diplomats and Star Fleet command each forbade such a mission, referring them to the other agency for approval. They appeared highly motivated to protect the mission and their reputations, but not the life of their very valuable captain in the field. A uniquely frustrated Mr. Spock was left to manufacture an unsanctioned course of action that would simultaneously save Kirk’s life and maintain diplomatic ties with Gideon. “We must acknowledge once and for all,” he later opined, “that the purpose of diplomacy is to prolong a crisis.” This, the captain of the Enterprise should have known quite well.

It was perhaps Jim Kirk’s own self-confidence and ego that fooled him into believing that he would not be subject to the stifling restrictions of policy, or the personal politics of the system. Unfortunately, his growing inability to conceal his disdain for certain members of Star Fleet and the Federation council created more troubles for the legendary captain. During the years following his return from his second tour in 2276, he was blocked, guarded and sequestered by elements that had consolidated power while he was light years away. Many of them had never even met the legendary captain, but had their judgement of him molded by others who had axes that they wanted sharpened.

Sitting behind a desk watching other officers and bureaucrats dictate policy exacerbated a vaguely forming mid-life crisis in Jim Kirk – a gathering sense of unease, disaffection and ennui that he could neither understand, nor had the capacity to examine properly. It was left to his oldest friend – at least, the one who was capable of understanding the emotions behind it – to bring it into the open. “When they offered him the Admiral’s position, I told him frankly that it was a mistake to take it,” Leonard McCoy said. “I knew he couldn’t survive there – with someone standing over him every day, watching every move he made. He needs to be out there doing it by the seat of his pants; getting dirty and maybe making mistakes – but for God’s sake, making a difference.” Leonard McCoy – far more so than Mr. Spock, was in a unique position to understand what Kirk was going through. “After that second tour, he told me he’d never go out again. That he was through. I knew he was full of shit. That man never could sit still.”(2)

Jim Kirk made a heroic effort of sitting still and playing the dutiful soldier. For five years he endured a clear diminution of his effectiveness at Star Fleet, but not without retaining a loud voice in the organization. He chose his battles carefully, if not always wisely. The chief friction among policy makers at this time was Star Fleet’s role in controlling the Klingon Empire’s push out into neutral areas beyond UFP jurisdiction. Kirk was among a handful of former service rank officers who had direct, personal experience with the Klingons. These men agitated behind the scenes for stricter measures to contain them, even at the risk of war. Another group of Admirals with less combat experience but greater seniority were in accord with the policy of UFP President Star-Ahn, advocating a provisional approach to encounters with the Klingons, wherever they might take place.

At this time – unbeknownst to Kirk and many others at Star Fleet, the Klingon Empire was undergoing a steep downturn in their fortunes. As early as 2268 the administration of the UFP was aware of the weakness of resources and ready labor within the Klingon sphere. The constant refrain among Klingon diplomats – often discounted by human politicians – was that their conquests were conquests of survival. Considering their subjugation and slaughter of innocent races, it mattered little that this was at least partially true; but the Klingons were indeed primarily victims of their own martial success. As their Empire grew outward, encompassing more and more worlds at more distant points, their personnel and supply lines were stretched thin. As poorer planets entered their sphere (races easily conquered by small fleets, or even single ships), the logistics needed to harvest raw materials and keep the population in line became an enormous drain on their resources and finances.

One solution to this problem was seen first hand by Jim Kirk and his crew, and hardened his deeply held antipathy towards the Klingons for the rest of his life. Around 2270, the Klingons took control of Crandall Orb, a planet rich with botanic and mineral resources, as well as a benign population of over 170 million inhabitants. After decades of diminishing returns from satellite outposts, the Klingon High Command invoked a new policy for the disposition of the latest conquest in their system. As they had done on many other planets, the local commandants chose a few million inhabitants for use in slave labor, the mining and harvesting of those elements that the Empire deemed important. Then, in order to keep the use of existing resources from being wasted on the indigenous population, the Klingons proceeded to exterminate the remainder of the people – over 150 million living souls – in just two short months. Over the next two years they stripped the planet clean, but while taking heavy casualties from the remaining slave population who felt they had nothing to lose. In 2273 the Klingons left the barren husk of Crandall Orb behind. The Enterprise was the first ship to respond to a distress call from the remaining inhabitants. Kirk called what they found “the single most awful thing I encountered in all my travels through the galaxy.”(3) Just one and a half million beings were left alive, with the rest killed by disease, starvation, exposure, and Klingon weapons.

Klingon mining and resource extraction reduced the surface of Crandall Orb to a swirling cauldron of sulphuric gasses and volcanic eruptions.

Some of Jim Kirk’s earlier idealism died with the people on Crandall Orb. As late as 2268 he was still optimistic about the possibility of working with the Klingons. His even-tempered actions during the manufactured standoff between Commander Kang and the Enterprise crew that year had given the Federation an entrée into secret, ongoing negotiations with the Empire. But his idealism was now gradually calcifying into rough-hewn bigotry. Additionally, the Federation council’s willingness to accept blatant Klingon misinformation about attempting to save the quadrant from a plague disease festering on Crandall Orb sickened him to the core. The political structure had been overrun by men and women who felt that the Klingon question would resolve itself without the need for active intervention. Their galactic Empire would collapse under the weight of its own overreaching ambition, the council reasoned, and the UFP would be rewarded with an insurmountable bargaining position. Meanwhile, as other worlds continued to endure the wholesale murder of the Klingon’s brutal dominion, all that the diplomats would advise – their policy of strength – was to stall negotiations and wait them out. The man who spent most of his adult life actively seeking safety and self-determination for beings of other worlds gradually began to lose his taste for a service that he believed was increasingly disinterested in his own deeply held principles.

In November 2280, Jim Kirk had a frank conversation with his immediate superior, Admiral David Cartwright about his future at Star Fleet. The two men had similar feelings about the bureaucracy of the Federation, but Kirk was never able to warm up to Cartwright’s deep, sometimes violent anger against the diplomatic corps. In particular, his frequent use of the term “political murderers” struck Kirk as somewhat hysterical, if not entirely unjustified.(4) They discussed the possibility of Kirk’s retirement, and Cartwright was sympathetic to his position. But he also implied that changes were coming in the UFP – positive changes that would mean a greater role for Star Fleet, and more latitude for them to dictate policy. Cartwright encouraged him to wait out the following year. Jim Kirk could not fathom what these changes might be, and resolved to follow through on his retirement from Star Fleet. When the enormous, jarring changes that Admiral Cartwright promised did eventually come to pass, Jim Kirk found himself unwittingly trapped in the dangerous heart of events far beyond his control.

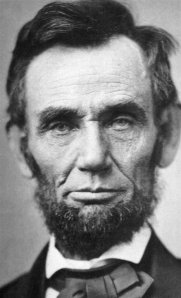

The decision to leave the Star service was the most difficult choice that James T. Kirk ever made. Star Fleet served many functions in his life. From his youth it provided him a template for his individual character. It gave him a direction and a goal for his overarching ambition to make a difference in people’s lives. It was the motivating force that kept him striving to follow the model of his heroes Theodore Roosevelt, Christopher Pike or Garth of Izar. And, most important of all – consciously or sub-consciously – it gave him a practical safety valve to embrace or reject life responsibilities as necessary. Duty, the highest calling – when he saw fit – could release him from any personal obligation that he deemed too restrictive to endure. Leaving these defining pieces of his emotional makeup behind would test his ability to live in a world that no longer contained a structure that had been built to protect young Jim Kirk from hurt, pain or loss.

For months Kirk struggled with his choice. “I’ve never had difficulty making decisions,” he joked during an interview on Vulcan Mediawave shortly after he left the service. “But when I decided to retire I was like Hamlet. ‘To be or not to be.’ That was the question.”(5) After three months of vacillation and doubt, his resignation was tendered on June 8th, 2281.(6)

My dear Admiral Cartwright,

It is profoundly disturbing to write this letter, but in my life I have found it is better to embrace one’s fears than avoid them.

I have decided to end my 30-year association with Star Fleet. We have discussed some of the reasons behind this choice, and I hope you will accept those reasons as genuine and honest.

The finest years of my life thus far have been in the service of an organization and people for whom I have nothing but admiration and thanks. If I can be of use to the Corps at any time, I am a ready servant of the cause we all believe in.

May the next generation look to what we have done during these years with respect and approval.

Faithfully yours,

James T. Kirk

SC937-0176CEC

On his last day at Star Fleet headquarters in San Francisco, Jim Kirk had his belongings packed into a trans-pod, threw a bag over his shoulder and walked towards his Aero for the final flight out. At the last moment before he took off, a friend caught him with some horrifying news. It was June 29th, 2281, the date of North America’s deadliest disaster in over 250 years: the Great Los Angeles Earthquake.

The Great Los Angeles earthquake destroyed at least a quarter of the city and killed over 80,000 people.

Skynet news service initially estimated a possible death toll as high as 100,000 (official tallies eventually came in at 88,000), with over 500 billion credits in property damage. After watching the first news broadcasts, Jim Kirk got into his AC and took off for LA. It was a gruesomely fortuitous event, sending the erstwhile Captain out on a life-saving mission instead of a silent, dour flight back to civilian life. His disaster training, and the organizational skills he learned while managing the holocaust on Crandall Orb were welcomed by the Planetary Disaster Team. For over a month, he worked – without charter – among the dead and the dying, sleeping here and there, filling in wherever needed, leading by example. He made an indelible impression on Dr. Jodin Sorex, a young MD, just beginning his career with the PDT. “It was amazing to see him in person, working directly with anyone who could help or needed a question answered. I saw first hand, the kind of leadership that made him so successful. In a way, it changed my life.”(7) Young Dr. Sorex took Jim Kirk’s passion for service to heart, first with the PDT, then as the President of the Federation Medical Council, where he led the famous think-tank that discovered cures for Vigan Correal Meningitis, Stifficoccus Novi, Xenopolysethemia and Securo’s disease. Many of their advances in life extension and disease control came out of the translation and study of the medical records of the long-dead Fabrini species, discovered and returned to Earth by the captain and crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise.

By early August, the city was in hand. For a short time, Jim Kirk thought he might carve out a position among the leaders of the PDT, but it was not to be. Instead, over the next two years he consulted regularly with the command structure of the newly commissioned Interplanetary Disaster Team, an organization offhandedly suggested by Kirk during his month in the City of Angels. Their first call to action came only nine months after Los Angeles, when rare solar flares interrupted all energy sources on planet Shoemaker-Levy 404. The quick deployment of the IDT saved thousands of lives there, and in subsequent years many more around the galaxy. Since 2281 discoveries in earthquake science and static-pulse correction have made southern California among the safest areas on Earth.

When Jim Kirk finally left Los Angeles, he scarcely had the emotional energy remaining to contemplate his separation from Star Fleet. He was tired, disillusioned, and uncertain of what to do for the first time in his adult life. He retreated to the small farm in the southwest corner of Idaho once owned by his Uncle Warren. Just outside the town of Hammett, nestled on the rich land carved out and irrigated by the Snake River was a deeded property of 12 acres, then still among the largest surviving private preserves in Elmore County. From the cabin on the site, a line of volcanic rock can be seen scratched into the high hills, a remnant from eruptions that blanketed the area with pumice and ash before the civilizations of Vulcan or Scalos were formed. This was the place that James came to most often while on earth, when his tolerance for responsibility was lowest, and hiding from the people who saw him as indefatigable and unflappable was his only option for a few moments of peace.

Warren William Kirk was a lifelong resident of the American west, steeped in the lore of the cowboys and Indians who had roamed those endless hills and fields in ages gone. A student of genealogy and history, he had traced the Kirk line back to the westward expansion of the continent, with gold prospectors and railroad men in their lineage. Among his distant ancestors was Elias Samuel Kirk, an engineer with the Central Pacific Railroad of California who was present at the driving of the golden spike that obliterated the American frontier by connecting the eastern and western rail systems of the United States in 1869.

On vacation at the cabin in the summer of 2240, seven-year-old Jim Kirk got his first taste of this history, as Warren told he and his brother tall tales of the great tribes of the Blackfoot, Nez Perce and Shoshone Indians. He projected his favorite old style celluloid films for the boys, 20th and 21st century dramas of western conquests, and battles between white settlers and the Indians who had lived there for hundreds of years. Names like Roe Traxel, John Wayne and William S. Hart meant nothing to the boys, but the stories of wide-open frontier spaces and the men who tamed them entered into young Jim Kirk’s brain, where they resounded noisily, waiting for a final frontier in which to reenact them. Among his favorites was the 2040 release Doc Holliday, which told the story of the famous 19th century gunfighter and his part in the historic showdown at the OK Corral in Tombstone, Arizona. Jim watched it so many times he could repeat the dialogue line for line.(8)

Now retired and at loose ends, the former Star Fleet admiral first busied himself with cleaning up the cabin, disused since his last visit there almost three years earlier. The art and artifacts that Jim’s uncle had collected over the years infused the space with the flavor and rhythm of western life. Among them were frontier-themed birthday gifts given to Warren by his brother George, a tradition Jim kept up long after his father died. When Warren passed on he willed the cabin and its contents to his nephew, who continued to expand the collection over the years.

On his first morning in Idaho, Jim made his way to town, looking for supplies. With a population of just 2100 people, he could never shake the feeling that in Hammett he was as far away from the heart of civilization as when he was while in the Mutara Nebula or at the edge of the galaxy.(9) It was not an altogether unpleasant feeling to him however; the abject loneliness of deep space often intensified his connection to the people around him. Jim Kirk spent much of his life trying to get away from himself, but rarely so far that he felt alone.

When Jim Kirk arrived in the sleepy town of Hammett, Idaho, it had been essentially unchanged since the mid-21st century.

In Hammett, a new business of any kind was a noteworthy event, and on Main Street, Jim noticed a small storefront gallery called Toni’s Western Antiques. Deciding to look for something new for the cabin, he threw his supplies in the Aero, crossed River Road, passed the local Indian herbalist, and walked through the door at 123 Main Street. What Jim Kirk found there was not art or artifacts, but rather a singularly unique opportunity to let go.

(Read part two of this excerpt HERE)

1) Handwritten letter from James Kirk to attorney Samuel T. Cogley, March, 2280. Kirk kept some correspondence with Cogley after the lawyer defended him from court martial charges in 2267.

2) Interview with Leonard McCoy by Alfonse Fago, unpublished, 2299

3) Official report on Crandall Orb from log of the USS Enterprise, 2273. This top-secret classified report was leaked to Hearst’s Federation News Bureau, in June, 2297. The outcry of a public who never embraced the Klingons as our allies resulted in the ouster of a series of UFP politicians.

4) Cartwright used the term in correspondence with Kirk, December, 2280. In his response Kirk was clearly put off, and deemed it an “unfortunate choice of words.”

5) James T. Kirk, Vulcan Mediawave interview, October 12, 2281

6) Kirk claimed to have tried “at least a dozen times” to write his resignation letter.

7) Interview with Dr. Jordin Sorex, Within the Kuiper Belt, December, 2299

8) Kirk’s simple knowledge of the people and history behind the OK Corral incident once proved highly dangerous. While exploring quadrant XR-71, a race of superior beings known as the Melkotians forced the Enterprise crew to participate in a recreation of the gunfight that they fabricated from his memories. Kirk’s personal log entry observed that it was “like living inside the movie.”

9) James T. Kirk, personal recordings for proposed autobiography, circa 2283

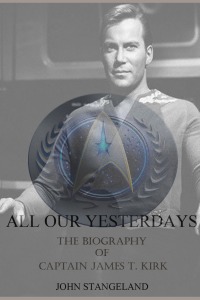

Welcome to the EtherBase portal for All Our Yesterdays, the newly published biography of Star Fleet Admiral James T. Kirk (2233-2293). Here you will find a wealth of supplemental material not included in the book, including chapter excerpts, interviews, rare photos, and unpublished writings available nowhere else. I hope you enjoy these posts, and encourage you to obtain your copy of All Our Yesterdays: The Biography of James T. Kirk through the I.S. EtherBase or via your home publishing hardware.

Welcome to the EtherBase portal for All Our Yesterdays, the newly published biography of Star Fleet Admiral James T. Kirk (2233-2293). Here you will find a wealth of supplemental material not included in the book, including chapter excerpts, interviews, rare photos, and unpublished writings available nowhere else. I hope you enjoy these posts, and encourage you to obtain your copy of All Our Yesterdays: The Biography of James T. Kirk through the I.S. EtherBase or via your home publishing hardware.